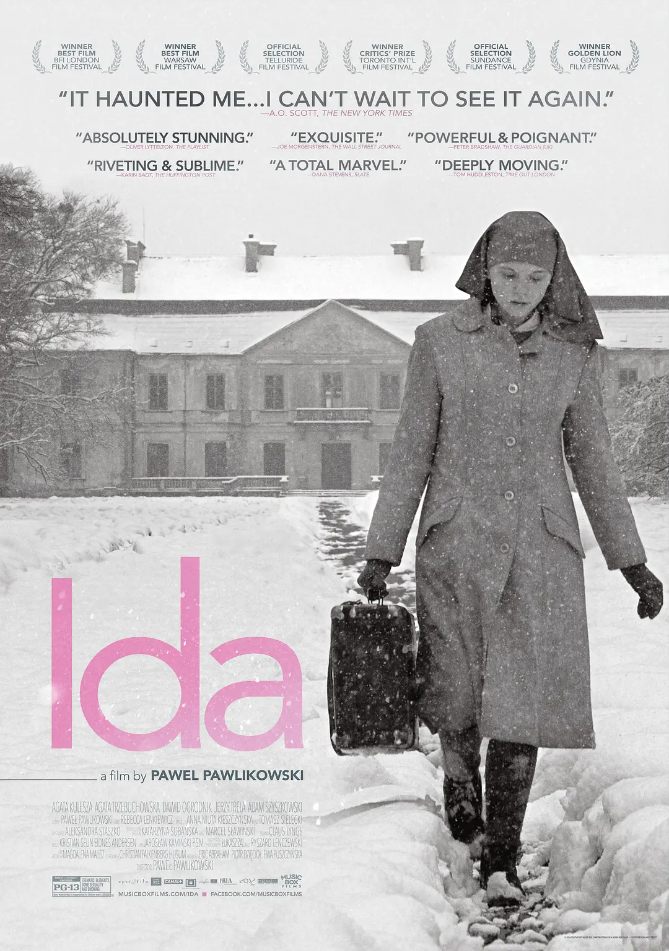

Ida History is fierce and unbearable

The Polish film “Ida”, also translated as “Sister Ida”, is a short, compact, but richly informative film.

The film is shot in black and white, which seems to be a popular color in the film industry these days, but it is appropriate for this film to reflect the dreary and dark times.

The film takes place in 1962, a time when the Cold War was raging, and when socialism in Eastern Europe was entering a more stable and dreary period. For Poland, after the Poznan incident, Gomulka came back to power and implemented limited reforms in Poland, and the atmosphere in Poland was freer and more relaxed than in the previous period, with a gentle breeze blowing.

The film’s protagonist, Ada, is an orphaned girl who grew up in a convent, and as she prepares to take her vows as a nun, she sets out on a quest to discover the mystery of her origins in order to seek the approval of her only relative, her aunt. The film follows Ida’s footsteps, uncovering a sad history and the reality of Polish society at the time.

The Catholic Church is an inescapable topic in Polish history, and it has played a crucial role in various key periods of Polish history. Poland is one of the few countries in Eastern Europe where Catholicism is practiced to a greater extent than in other countries. The Church became the spiritual pillar of the Polish people and, of course, dictated their actions. Even during the decades of communist rule, the Catholic Church remained deeply rooted in the people, which is extremely rare among socialist countries. Communism saw religion as a natural enemy, and churches in other countries of Eastern Europe were either completely banned or suffered heavy blows and were dismembered and transformed into the so-called Three-Self Patriotic Church. In Ukraine, too, the Catholic Church was forced to merge with the Orthodox Church, and those who did not comply were exiled.

Poland also went through a dark period when a large number of churches were closed and a large number of clergy were arrested, but after all, the Church was preserved, and the people of Poland were left with spiritual solace and the spark of freedom. The Polish bishop at the time said, “We are not allowed to place anything related to God before the altar of a tyrant. Never!” He, too, was arrested, but the words inspired the Polish people.

Ada grew up in such a convent, and when she turned twenty in 1962 and could take her vows as a nun, she probably had no doubts about her choice of life, a life in which she would serve God in a convent. She was an orphan, she did not know her origins, she was a child born in a troubled world and had accepted her fate. When she heard that she was Jewish and that her parents had died at the hands of the Nazis, she was a little surprised and wanted to visit her parents’ graves before she became a nun, to do her duty as a human being. Accompanied by her aunt, Ada sets out to find her parents’ bones and to solve the mystery of her origins.

Ada, who has never been out of the convent, faces a world she is not familiar with, a world far more complex than the one in the convent. And even more painful is that she has to go after history and face the tragic truth. These truths have been buried, just like her parents’ bones, and no one wants to uncover them again except for their loved ones. History, after all, has too much cruelty and too much unpleasantness. The Poles have the pain of being ravaged by the Nazis and the memory of the Katyn tragedy caused by the Soviet Red Army, but they also have an unconscionable behavior when it comes to the Jews. The good thing is that the film confronts this history head-on, and at least there is some repentance.

Everything that Ada has built up in the convent over the previous twenty years is in jeopardy. She is torn between her family love and religious feelings, she has worldly ties and hesitations about her future. The fact that she was Jewish and her devotion to Christianity also conflicted in her mind. How much more did the history of her parents’ tragic death shock her? The murderer who killed her parents left her lifeblood behind as well.

More difficult than her to accept that history, but her aunt, the woman who was once called “red-haired Wanda”. She appeared to be unusually competent and ruthless. She was also Jewish, but had joined the partisans and was now in a high position as a judge, living a good life alone. Her private life is quite chaotic, even in the journey to accompany her niece Ada in her quest for history, but also forget to have fun, so that Ada grew up in a convent to look at her sideways. She also acts quite domineering, but in that kind of society, not to use their own power, and how can successfully help their niece find the bones of their parents?

At first Wanda is also cold to her niece Ada, but the process of finding the bones of a common loved one makes a kinship budding between them. For the final truth, Wanda seems to be more difficult to accept than Ada. Along with her sister’s brother-in-law, her son died. She had known more than Ada, but had been reluctant to accept the truth inside, perhaps hoping for another outcome. When she heard the killer’s own words about the circumstances, holding her son’s bones in her hands, everything she had built up inside collapsed. Her final and decisive action was decisive and simple, without a hint of hesitation, as she usually does. The music she played was perhaps a nostalgic reminder of her past life?

In fact, she should have understood the cruelty of this chaotic world, and the horror of the truth. Since you have the courage to go after history, you also have to accept the cruelty of history. As a judge of an emerging red regime, she held the power of life and death of many people in her hands. According to her, she once sent a large number of reactionaries to the execution ground in order to suppress the enemies of the red regime. That is why she was nicknamed the “Red Vanda”. Whether her death was a protest against the Nazi and Polish atrocities against the Jews, or a confession of her own murderous past, is a question that cannot be answered.

Far less decisive and determined than her aunt Wanda, Ada was torn between the world and God. She had already gravitated to the secular world, for identity would have made her find it difficult to survive in the convent. But her aunt’s final, decisive action pushed her back into the convent. Even her first taste of love made her feel that the worldly life was nothing more than that, and did not increase her longing for the present world any more. But when she returned to the convent, her mentality had completely changed, and she did not take her vows as a nun with her companions. As a girl raised in a convent, pure and unaware of the world, how could she have imagined that there was so much entanglement behind history? Wounded by the ferocity of history, she had to reorient the coordinates of her life.

History is too ferocious to look back and fear being wounded.