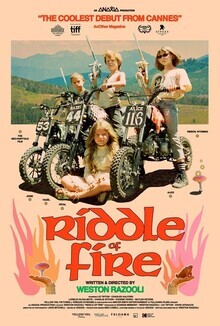

Riddle of Fire

“Riddle of Fire” is the kind of cinematic bedtime story whose whimsical tone makes it easy to overlook its many keenly crafted intricacies. The feature directorial debut by writer/actor Weston Razooli works through a charming conviction: Three kids—brothers Hazel (Charlie Stover) and Jodie (Skyler Peters) and their friend Alice (Phoebe Ferro)—rumble down a country road on their motorbikes to an OTOMO warehouse armed with paintball guns and gummy worms. They fearlessly infiltrate the stockroom, procuring a box simply marked “Angel.” The only resistance they meet is from the manager, whom they mercilessly shoot at before triumphantly thundering back home on their motorbikes.

Throughout “Riddle of Fire” we’ll find the many seemingly insurmountable obstacles these rambunctious kids can overcome. One barrier they can’t break down, however, is the parental password protecting Hazel and Jodie’s television. See, Angel is a game console. And if the trio want to play it before their summer soon ends, then they need Hazel and Jodie’s sick mother Julie (Danielle Hoetmer) to unlock the television. She’ll only do so if they can make a special kind of blueberry pie. What follows is a difficult odyssey requiring the trio to first acquire a secret recipe from one adult, then to make a run to a grocery store that turns up every ingredient except for a speckled egg: The last egg is taken by an unpleasant, as the kids call him, Woodsy Bastard—who they tail to the forest in the hopes of stealing it back.

Phrases like “Woodsy Bastard” are indicative of Razooli’s willingness to imagine children as full-fledged human beings: These Peter Pan-esque characters are foul-mouthed runts unafraid of confronting morally bankrupt adults yet are equally prone to stirring further trouble through their flights of naiveté. They are neither too precocious nor too innocent. The result is an exhilarating concoction of fairy tale and fantasy, kissed by a gooey daydream wonderment that is made possible primarily through the knowing performances provided by these young actors.

That sense of imagination is further translated from the warm lens’ Kodak 16mm coat and the rebellious score: They imbue the woodlands setting with a mystical air. The trio find further help from Petty Hollyhock (Lorelei Olivia Mote), a kind of flower child who seemingly exists in another time in another place. They need her aid in the face of the Woodsy Bastard aka John Redrye (Charles Halford) and his poaching friends Anna-Freya (Lio Tipton), Suds (Rachel Browne), Kels (Andrea Browne), and the dimwitted Marty (Weston Razooli). In a film accumulated by good-for-nothing adults, this quintet is the worst.