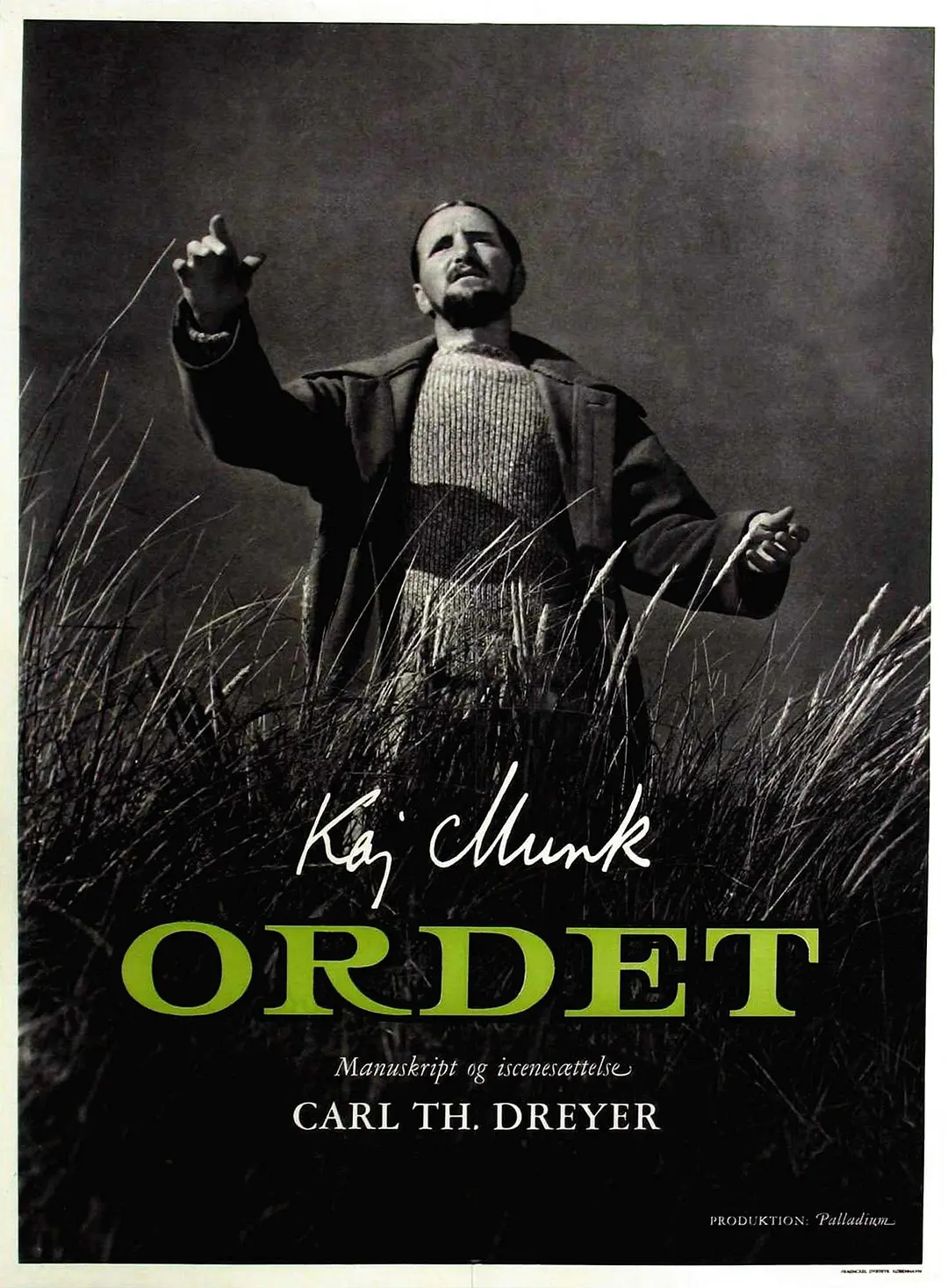

Ordet The Restoration of Christianity

Just as a great philosopher always says the same thing over and over again, so a great director often repeats the same theme.This theme, for Bergman, is the agitation of people’s souls after losing their faith; for Antonioni, it is a modern man wandering back and forth in the ruins of post-industrial society; for Bresson, it is the transcendental experience brought about by the formal style of the film; for Deleille, it is the step-by-step erosion of faith by human arrogance, so that the religion preaching love gradually turns into struggle and persecution.

The decline of Christian faith is an indisputable fact in Western society since the Reformation. This decline manifests itself philosophically in the philosophizing, psychologizing and experiencing of religion on the one hand, and in everyday life in the general lack of faith and loyalty to God on the other, with faith becoming an additional pastime for modern people to enjoy their worldly lives contentedly, and in the words of the Bogan farmer in The Promise, “I pray only when I feel worthy “. In Western philosophical and theological circles, calls for a return to the original Christian faith have also been heard from time to time, from as far away as the “Christian passion” called for by Draper’s Danish compatriot Kierkegaard, to as close as Barth’s neo-orthodox theology. The former, through its critique of modern Christianity, calls for a return to a time when the original Christian faith was flesh and blood, alive and passionate; the latter again grounds the Christian faith in the truth of historical revelation. Both can be seen as distant echoes of Pauline theology in the modern world. The faith of the apostle Paul was founded on the resurrection of Jesus, for the miracle of Christ’s death and resurrection illustrates Jesus the Savior, the only Lord in whom we trust. The core of people’s act of faith is love, which is the whole surrender of oneself, and only through love do people have faithfulness and the possibility of salvation.

From Pasolini’s Gospel of Matthew to Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, the theme of Christianity in films can be described as endless, but the only one I have seen so far that calls people back to the original Christian faith in the sense of Pauline theology is Deleille’s The Promise.

The Promise” tells the story of how two families whose children love each other because of incompatible beliefs cannot be united due to a miracle and are reunited. The eldest son, Mikkel, is good and hard-working by nature, but does not believe in God. His wife, Inge, is a devout Christian and has an important influence in the family. The second son, Johannes, gradually “developed inwardly” as a result of his theological studies and became insane, claiming to be Christ of Nazareth and repeating the words of the Gospels all day long in the house. His face and expression resembled the Christ one sees in the icons. Anders, the third son, and Anne, the daughter of Peter the tailor, fall in love, but are thwarted by two families who do not share the same faith. Finally, Miguel’s wife Inger dies in a difficult childbirth, and the family is plunged into deep grief when Johannes leaves behind a passage from the Gospels and goes missing. At Inger’s funeral, Johannes suddenly appears, having regained his senses, and with the joint prayer of him and Inger’s daughter, Inger rises from the dead, awakening the faith of all present again with a miracle.

Rather than being about miracles, the film is about the truth of faith. Through the miraculous spectacle created by the film, Delayed calls for a faith that is so real that it can be seen (as Johannes often says in the film, “I see ……”), a faith that is so real that it dares to pray for the resurrection of the dead.

The miracle of Jesus raising the dead appears several times in the Gospels, and the film also features a biblical illustration of Jesus raising the dead. Obviously, “The Promise” intends to carry out this story. In the film, miracles have been a recurring theme, and those who lack faithfulness to the faith believe that “the time for miracles has passed,” “miracles will never happen again,” or “Jesus’ miracles are the exception. “On the other hand, God could have performed miracles, but he didn’t. Why not? Because miracles would break the laws of nature. Of course, God does not break his own laws.” Trying to reconcile faith and reason compels one to adopt this Spinozan philosophical interpretation of miracles. Miracle belief is even more severely rejected by modern science, as the doctor in the film says to the farmer after turning the woman in labor, Inga, around (and then she dies unknowingly), “Who do you think is responsible for tonight’s miracle, your prayers or my healing?”

Just as important as the miracle is love, which is talked about several times in the film. There is a conversation between Inger and Mort about love:

“Grandpa, I think the most important thing is to love each other.”

“There are limits to love, Ingo.”

“Grandpa, can you tell me if I’ve ever really loved in my life?”

“I’ve loved about 10 times.”

“Ah, Grandpa, it seems you’ve never really loved. My little grandpa, you know everything in this world, except love.”

In the movie, Mikel loves his wife Inga deeply, but Mikel does not believe in God, and Inga says to him, “You are very kind, but just being kind is not enough.” A person who has only worldly love and goodness based on reason is vulnerable, especially when fate strikes.

The focus of the film is on how faith, which does not believe in miracles and lacks love, becomes corrupted in the face of human arrogance, and how faith becomes a battle and even persecution (here, Delayed continues the theme from “Joan of Arc” to “Days of Wrath”), which is reflected in the confrontation of faith between the farmer Bogan and the peasants represented by Peter. They both claim that their faith is the true faith, but both can hardly hide the emptiness of their faith, for which they can only fill it with arrogance. Mott’s reason for not approving the marriage between his son Anders and Anne, the tailor’s daughter, is revealed by Mikel, “You are worried that Anders’ faith is not as strong as Anne’s!” It would be a shame for Motel if his son were to convert under the influence of Anne, how could the proud farmer lose to the peasants. Peter the tailor refused Anders, ostensibly because of his different beliefs, but in fact because of his pride, thinking, “It would be a great thing if we, the little people, could overcome the Bogan farmers. Later, Mott, knowing that his son’s proposal was rejected, surprised everyone by taking Anders to propose again, also because of the pride in his heart, “What? I, the son of a Bogan farmer, can’t marry that tailor’s daughter”? For Mott and Peter, faith becomes a battle for their honor. One of the scenes in the movie is a very clever way to show how the unified Christian faith is divided by the pride and conceit of the people: Motel brings Anders to Peter’s house again to propose marriage, and runs into “those nasty peasants” having a prayer meeting. Finally, towards the end of the prayer meeting, the people start to sing hymns, when the camera fixes the camera on the model and his son. It is clear that the faith is the same God, the hymns praised by the same God, then Mott’s face is all rigid, uneasy and disdainful look, with the surrounding sacred hymn music to form a strong irony between. More interesting is the next scene, in which Peter tries to make Mott “turn to them” by grabbing Mott’s shoulders with both hands and saying something about how only our faith can make salvation possible, while Mott instinctively resists by leaning backwards, which is very similar in effect to the actions of people resisting the temptation of the devil in some religious paintings. When faith is taken over by inner arrogance, man becomes the devil. In the next scene, this is even more evident: before Mott leaves, Mikel calls to tell Inger that she is dying in childbirth. Peter wants this fact to prove to Mott that his faith is unreliable, going so far as to “wish in the name of Jesus” that Inger would die in childbirth. Faith and persecution through faith, angels and demons, are only a short distance apart in the heart of man.

Johannes is a key character in the film, and his multiple identities make him appear ambiguous. First of all, he is a seminary student with psychopathic symptoms, who sees himself as Jesus and talks nonsense all day long, but he is also a faithful person with true faith like Ingo, who comes back to his senses at the end of the movie, so his faith is not based on insanity. Johannes is somewhat similar to the holy fool in Russian culture. In the end, whether from the character, shape or plot arrangement, Johannes does have the shadow of Jesus in him. After Inge’s death, he leaves behind a passage from the Gospels before going nowhere:

“My time with you was short.

You will seek me.

Where I go you cannot go.”

His mysterious disappearance amounted to some form of death. All the conversions and miracles occur after his “death”, including Peter the tailor’s sudden realization of the falsity of his faith and his coming to Mott for reconciliation, and Ingo’s subsequent resurrection. The film intends to symbolize the story of Jesus’ martyrdom on the cross and his resurrection three days later through Johannes’ “death” and subsequent resurrection (after regaining his sanity). It is through the double miracle of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus and the resurrection of the dead that Draper calls people to return to the original Christian faith.

Making movies about miracles is not a crowd pleaser, and audiences can easily be turned off. Many miracles in movies are related to faith, but people always feel that the director’s narrative has gone wrong and cannot be rounded off, so he has to bring in miracles to save the day, such as in “Bin Vu”. De Leye handled the miracle as an inevitable result of the film’s narrative, laying a full foundation in the audience’s mind with the help of the “archetypal narrative” of the miracle in the Bible. In terms of visual language, Delayed shows the contrast between the miracle and its occurrence, thus strengthening the persuasive power of the miracle. In the outdoor scenes of the first half of the film, the sky is always gray and uncertain, and on the far side of the road where the carriage drives, a hillside is covered with weeds dancing in the wind, and a small gray cross stands in the distance, symbolizing the decline of the impression. It is only after Johannes leaves (symbolizing the death of Christ and the reappearance of faith) that the sky outside begins to brighten. This effect of light is also applied to the scene in which the miracle takes place. Inside the spiritual chamber, the intense sunlight from the window falls through the curtains onto the coffin of Inge inside, a light that has a rich connotation. In the history of Christian theology, Augustine’s theology of illumination has had a great influence, in which the eternal light of God shines on man’s finite reason before he can believe. Inge was as strong a believer as Johannes, and her post-mortem image did not feel dim in any way, but was bathed in a holy light, as if she had been truly in the arms of God, and her subsequent resurrection seemed natural.